MUEVO Interview x elculture.gr

(ENG Version)

Where can you find an entire room painted by Theophilus in Athens?

I visited the Museum of Modern Greek Culture, met with its people and was impressed by this museum that is right under our noses, just by Monastiraki metro station.

By Stelios Parris

There is a museum right under our noses, a “multiplex” I would say, right next to Monastiraki station, at 10 Areos Street, which I visited and admired, and through which I learned a lot about modern Greek culture above all.

On a Tuesday, when the Museum of Modern Greek Culture is closed, I was given the opportunity to be guided by its director, Ms Elena Melidi, and Michalis Doukas – one of the key contributors to the implementation of the museum’s museography. I found myself in a frenzy of work with handlers taking items out of boxes for the museum’s store, curators setting up exhibits together with conservators, and me roaming from one building to another and chatting with almost everyone I encountered on my way. The Museum was inaugurated on December 22 and immediately began its operation with three large buildings already open to the public from the total of eleven that will open their doors by summer – the reason why I prefer to call it a “multiplex”. The Museum itself is like a historical neighborhood of the 19th century that is preserved almost intact.

Elena, tell me a little about the history of the Museum of Modern Greek Culture.

“It is one of the five major museums of the Ministry of Antiquities, under the General Directorate of Antiquities and Cultural Heritage. One of the oldest historical museums of the country, it was founded in 1918 as the Museum of Greek Handicrafts with painter Konstantinos Maleas as its first director – it was formed by very prominent personalities of the time. The museum was first housed in the Tzisdaraki Mosque, in Monastiraki Square, which also falls under our jurisdiction. Tzisdaraki Mosque will present the story of how this museum was born, how it grew, its entire historical course together with its collections policy, which was influenced by shifting social-cultural and political-historical developments throughout time.”

[Fig. 1: Detail from a display case in the exhibition “For our Faith and Worship” – the sliding magnifying glass allows the audience to observe every detail on the small votive plates (“tamata”) © Vassilis Rebapis]

I hadn’t even realized that there was a museum here – I always passed by on my walks and I remember seeing all the works that were taking place.

EM: The expropriation of all these plots and houses started in the 1990s. They were originally expropriated and the plan was to level them in order to present the archaeological sites beneath, but later, it was decided to house the Museum of Modern Greek Culture, then called the Museum of Greek Folk Art. It changed its name in 2018. What you see as both the restoration of buildings and the operation of a museum started in the context of the last two NSRFs. With the NSRF 2013-2017, we implemented the restoration of the buildings, the studies we needed for the presentation of the permanent collection, and the preservation of 3,000 artefacts. The museum’s exhibition was implemented with the second NSRF 2014-2020.

A woman comes quickly, approaching Elena and Michalis.

EM: In this building here, Ms Panagiota Andrianopoulou, Head of the Museum’s Collections Department, is responsible for curating this particular section of the exhibition.

Panagiota Andrianopoulou: This exhibition is titled “For our Faith and Worship”, and explores customs found in the sections “Cycle of Time” and “Cycle of Life”, as well as the relationship between popular worship and official church worship.

EM: The secularization of the ecclesiastical function, or, in other words how the Orthodox church and our faith are met by popular customs and religious traditions.

Panagiota, can you tell me about an exhibit that will make me understand more about this “secularization” ? –I haven’t heard this word in years.

PA: From the Cycle of Time, I would like to highlight the two costumes from the carnival event “Jenissaries and Boules” in Naoussa, which also show something important that our museum is trying to accomplish: to bridge the material with the immaterial. We are essentially talking about an event through its special costumes, that were traditionally made by specialized craftsmen with a unique technique, together with their special masks, both of which constitute intangible cultural heritage registered in the national index. From the Cycle of Life, an example of secularization would be the clay baptismal font. It dates from the end of the 19th century, the time when baptism could also be performed in homes – which was also a completely transitional time when baptism starting becoming a church ceremony.

[Fig. 2: From the exhibition section: “What Were They Wearing? What are you wearing?” | The “Mountafissa” bridal costume and other traditional costumes | © Vassilis Rebapis]

[Fig. 3: From the exhibition Section: “What Were They Wearing? What are you wearing?” | Embroidered nightgowns in a special display case containing drawers with built-in multimedia applications that visitors can open to discover more exhibits from the collection | © Vassilis Rebapis]

And while we were talking about the material and the immaterial, I turned to look again at Michalis Doukas. We talk about intangible stuff, but it’s time to meet the master of materials and construction. Who is he?

Tell me, Michalis, how are you involved with the Museum?

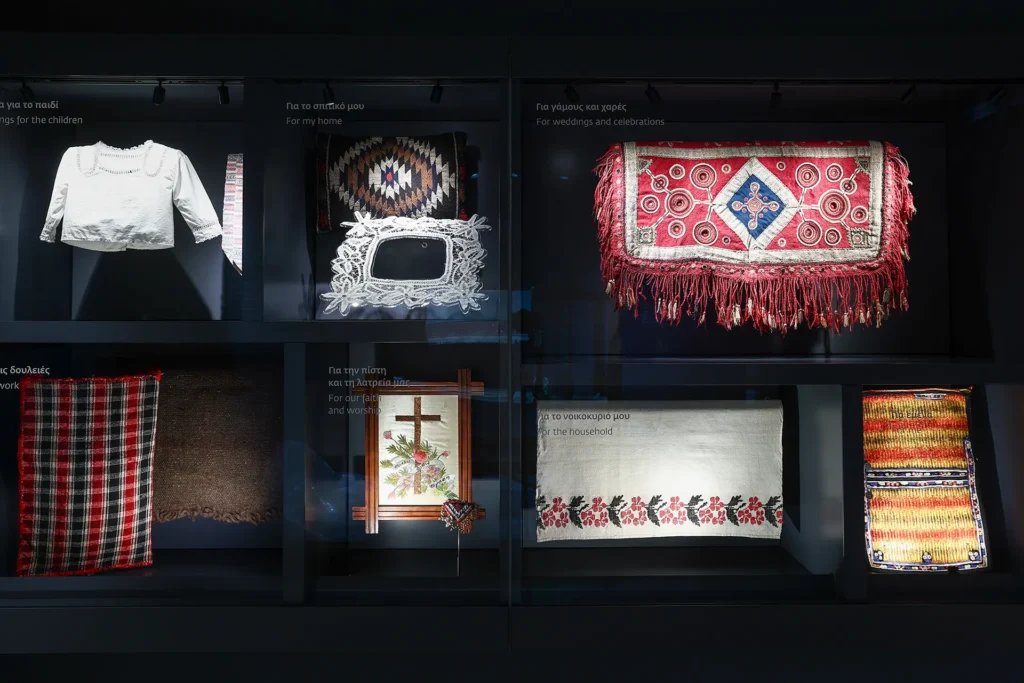

Michalis Doukas: I am the Managing Director of MUEVO, the company that designed, produced and installed all of the museum’s showcases and exhibition structures, including their lighting equipment –about 260 showcases and special structures in total. MUEVO won the international competition that took place and then we proceeded to analyze the museographic study, proposing technical solutions to build all these showcases that you see. All showcases that have been created for the museum are custom-made, so each and every one of them is unique.

Our goal, together with with a team of museographers, architects, conservators, etc, was to achieve balance between the museological and museographic study, the design of the museum, the presentation and protection of the exhibits, as well as the functionality of our structures. Because functionality is an important part, especially for the Museum staff, who are called to manage all these constructions throughout their lifetime.

EM: We wanted a simple, modern and at the same time neutral environment for our exhibits. There is a large diversity of materials in the showcases with unique colors. They are all very special objects and their reception is aided by the neutral environment, with the corresponding lighting and narrative.

[Fig. 4: Showcase containing handicraft pieces in the section “How did they work?” How do you work?” | © Vassilis Rebapis]

How long did it take for MUEVO to design and construct everything?

MD: It took about three years to implement this project amidst the pandemic. It is the first time that honeycomb is used in museum constructions in Greece – a relatively new material in the museum field, of excellent quality, which provides protection to the exhibits while contributing to the insulation and stability of the constructions. The painting of the constructions has all been done using special techniques that never give the feeling of aluminum or metal; we aim to highlight the exhibits.

I see the exhibits that are from materials that wear out the most. Paper, fabric, wood.

EM: That’s right, organic materials are rather sensitive.

MD: The showcase’s internal micro-environment is something that to which we have paid particular attention. All the materials and paints that have been used do not emit any harmful substances that could affect the exhibits.

EM: The buildings that make up the museum used to be houses. Small compartmentalized houses with rooms where we would have to put showcases from one end of the wall to the other so that they would be as “light” as possible. A single surface that the visitor will see so as not to disturb the environment of the exhibition.

MD: And by achieving utmost transparency, we harmonize the showcases, whilst respecting the historic buildings, and they both work together so that this whole exhibition can be done with large openings. Which is also a very difficult thing, because having such large openings is something that needs excellent technical knowledge.

EM: And as you can see the showcases are truly light in the museum space, they do not “burden” the exhibition environment.

From my point of view, it seems that you gave houses a museum function.

MD: And the more simplicity you have, the more know-how is hidden behind it to achieve such a result. We had to deal with various issues in these old buildings: we had to run wiring and ventilation; our constructions had to pass through very small access points so they had to be assembled on site. Plus, this project was implemented during the difficult period of the Covid-19 pandemic, and there were difficulties in importing materials or finding things that we wanted; nevertheless, we succeeded and overcame all obstacles.

EM: It was a complex process but I think that the result paid off.

[Fig. 5: Exhibition room in the section ‘Where did they live? Where do you live?” | © Vassilis Rebapis]

I really enjoy interactivity in museums and you clearly planned for that.

EM: It is a very human-centered museum. You can feel that this museum was designed by people for all different kinds of people. We had conducted an audience survey before we started setting up this exhibition and asked people how they would imagine a museum for modern Greek culture. We were referred to two main principles. One was that everything presented should somehow relate to our time, and the second was that all exhibits should be part of a narrative context. Especially given that they have no archaeological value: they are utilitarian objects, mostly transferred from hand to hand, from person to person. So, we had to present the historical path of the object to make it attractive to the audiences, so that the visitor will stop and listen to the story of the object.

So, I won’t see antiquities in this museum?

EM: You will only see some outside. Internally you will see what we refer to as cultural goods of modern culture. For us, cultural heritage is identified with the last two centuries, i.e. from 1750 to 1960, the period which the vast majority of objects in our collection date from, because this is essentially the historical period where the Greek cultural identity is formed and flourishes, We address all age groups and small visitors with interactions, what we call “edutainment”

MD: This museum succeeds in telling stories and that is very important. It succeeds to explain visitors what happened in the past and how we still find this teaching in front of us, both now and in the future, and this is a great success – it will make visitors come back to this museum many times.

[Fig. 6: From the exhibition section “How did they work?” How do you work?” | Embroidery craftworks presented together with an interactive digital projection in the “back” of the display case | © Vassilis Rebapis]

[Fig. 7: From the exhibition section “How did they work?” How do you work?” | Exhibition system with double-sided vertical drawers | © Vassilis Rebapis]

You with MUEVO have also collaborated with other European museums, have you detected any changes in the Greek museum landscape?

MD: I believe that culture is a key to development in our country and I see that the museum concept is progressing a lot in Greece. It’s starting to take the place it deserves and this project here is a great example – made only of the most prime materials and implemented by a Greek company, when museum projects of this scale and quality were realised by foreign companies in the past.

Is there a specific pathline that visitors should follow in the museum?

EM: We are talking about ten different exhibition sections, each one of them dealing with a certain manifestation of modern Greek culture: clothing, decoration, work, entertainment, faith, accommodation – everything is interconnected and relates to the central idea, that is the contribution of modern Greek culture to the formation of Greek identity today, both individual and collective identity. So, this central idea dominates throughout all exhibition sections, which are connected with each other. However they are also independent at the same time, so no matter where visitors move, they will receive the exact same messages, all pertaining to the concept of modern Greece.

I started roaming around outdoors and indoors. I saw objects that looked as if they were almost floating, I listened to sounds, watched video projections.

Let me ask you, Elena Melidi, what is the name of this room? Because as soon as I entered here, it felt like Easter.

EM: (laughing) Here is the Cycle of Time, where we begin with Saint George and Saint Demetrios, who mark the beginning and the end, and here we enter the Twelve Days – Evangelism – Easter. The projection you see on the wall here is the Epitaph Procession from St. Nikolaos of Ragava in Plaka – it is our own production which we shot last year to show the epitaph ritual that takes place on Good Friday. We have a total of 48 digital interactive exhibits. Each room also has its own digital exhibits as per our original idea. The logic behind a modern museum is incorporate the latest technologies in order to support the interpretation of the exhibits, harmoniously integrated in the exhibition.

MD: Have you noticed that you can’t see your reflection on the glass of the display cases no matter how close you get? We have used antireflective glass, which reduces the visitor’s reflection by 99% so that they can focus entirely on the exhibit.

EM: One of the particularities of the exhibition is the mounting of the objects – not particularities exactly, I’d rather call them novelties if I may, and mounting was something that particularly concerned us. Our aim was to reveal as little as possible, so as to give the feeling that the object is free in the display case and so the visitor can see it from any angle they choose and interpret it accordingly as they wish.

MD: It took some special handling so that the honeycomb on the back of the display cases would fit perfectly with the artefacts mounting supports.

[Fig. 8: From the exhibition Section “How did they have fun?” How are you having fun?’ | The room with the shadow theatre figures of Karagiozis | © Vassilis Rebapis]

I saw many different artefacts, some familiar and some unprecedented, such as the 19th-century head-rings for the mentally insane (“Krikoi Frenovlavon”), relics that were brought from Asia Minor to protect the patients. Or the figures of Karagiozis by Vasilaros, which recorded all of life’s joys, anxieties and sorrows, such as the “Great hunger of July 1942″, “Fine work”, “Fotis Rammos commits suicide in 1938”, which curator Niki Dafni pointed out for me.

In the outdoor area, one will see the Gate and the staircase of the mansion of Chomatianos Logothetis (English Consul) from the first half of the 18th century – one of the few Ottoman remains that still exist in Athens, as well as the church of St. Elissaio, where Alexandros Papadiamantis would chant.

A museum divided into sections that takes you on a journey through the history of modern Greek culture by asking the following: Where are you from?/ Where are we from? What do they believe in?/what do you believe in? Where did they live?/where do you live? How do they have fun?/How do you have fun? What work did they do?/What work do you do? What were they wearing?/ What are you wearing? Objects and exhibits that speak for themselves about the historical events of our country.

[Fig. 9: Theophilos’ room – from the fresco room in the Zolkos house in Napi, Lesvos island (in the Exhibition section “Where did they live? Where do you live?”) | © Vassilis Rebapis]

Closing this article, I would like to mention a magical moment that reveals the very essence of what a museum is about after all. At a certain point when everyone was hurrying to finish their tasks, I found myself alone, marveling at a room that is entirely painted by Theofilos. Then the museum guard, Giorgos, approached me and spoke to me, saying:

“This is my favorite room, because it is one of the most valuable exhibits in the entire museum. This is something unique, Theophilos painted this, when he went to stay in that house in Mytilene, he painted it in parts. At some point in the 70s, the new owners of the house walled it off with the intention of selling it, but with the excuse that they would exhibit it at the Hellenic-American Exhibition. The Greek government bought it for 10 million drachmas, a very significant amount for that time.”

It is truly admirable when all the employees in a museum can also act as tour guides, I tell him, and he replies: “I’m a day guard, I don’t know everything obviously, but when you work in a museum you have to know what it shows to the visitor”.

For me, it’s nice when every museum can function as a school, and in the case of the Museum of Modern Greek Culture, I was happy to conclude that its people, together with MUEVO’s team set up a “multiplex” like a modern school that teaches us by time-traveling us through objects of daily use in modern Greek history. It is a museum that is certainly worth visiting with our families, our foreign friends, and even alone on a magical walk in Monastiraki, that usually leads us without realizing to the Acropolis and the paths masterfully carved by Pikionis.

*The article was originally published on 27 February 2024 under the following title:

“Tour in a historic neighborhood of the 19th century that is preserved intact to date or in other words, the impressive Museum of Modern Greek Culture”

Click here to read the original article in Greek.